Cine-Royal: This "Blue Piano"

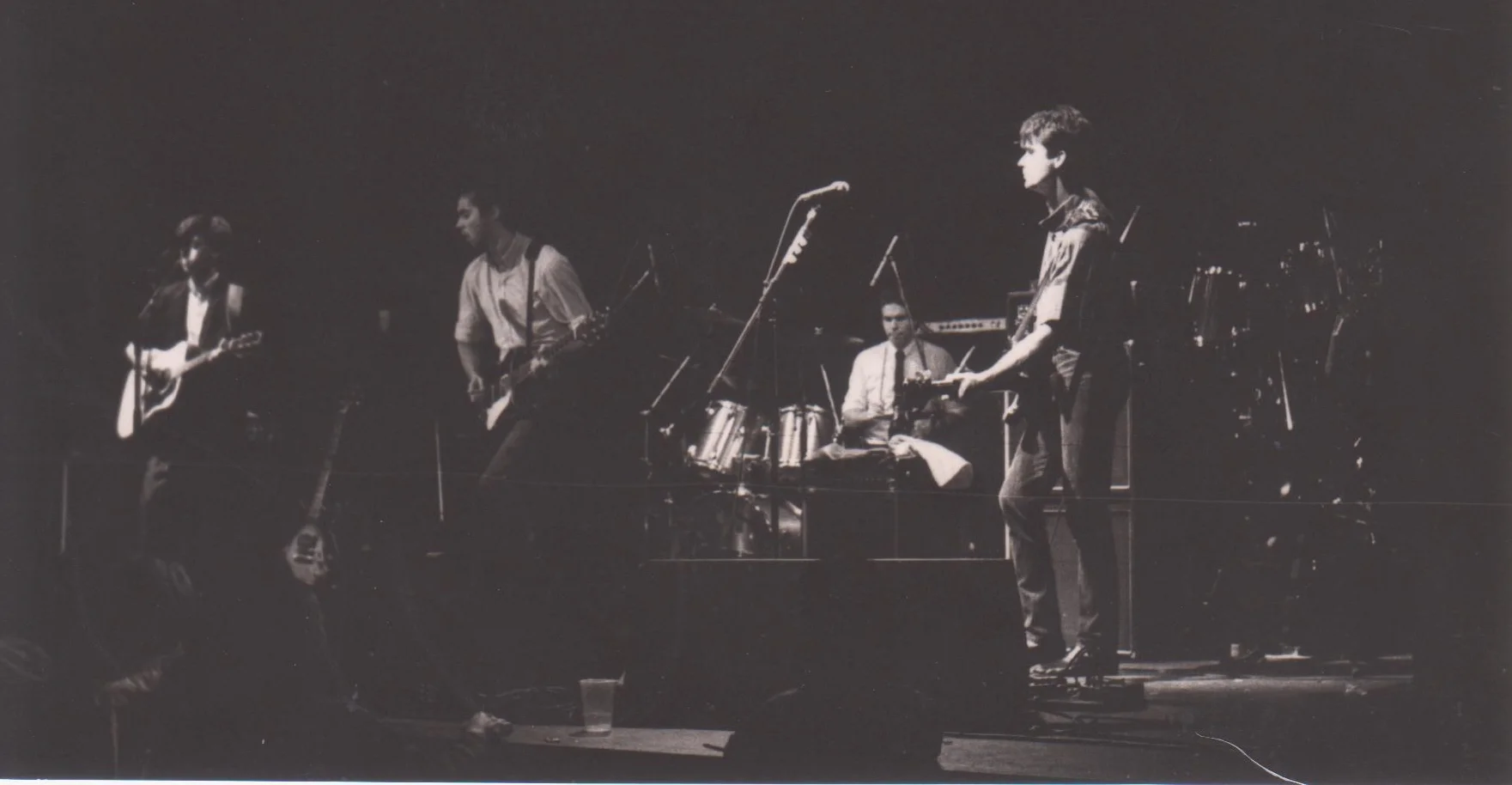

L-R: Normal Mackay, Colin Cahill, Ken Ashdown, Stephen Lamont

Live at Club Soda, Montreal

je me souviens: the official biography

English comedian Jeremy Hardy once remarked that we can’t help turning into our parents: “Young people’s music today... well, it’s not proper music, is it? No real tunes, no words, you can sing along to... Now, in my day, we had the Pistols and the Buzzcocks...”

Also in my day, we had the first great flowering of rock ironists. Not like your Clearasil generation now, when everybody who’s even made a day trip to college will churn out a forced one-liner amid their emo blarge and think it makes them the successors to the Algonquin Round Table. (Alanis Morrisette, kiss my royal Irish arse.) No, this was pioneered and perfected by Brits who purveyed that bittersweet blend of poignancy and self-deprecation as if they’d ingested it along with mother’s milk. Because, being Brits, they had.

But this doesn’t mean it was an Anglo-Saxon phenomenon. In fact, after the Godfather of Wistful Smirk, Ray Davies, every one of the prime exponents has been a Celt. The New Wave gave us Liverpool-Irish Elvis Costello and Pete Shelley of the Buzzcocks, whose real name Peter McNeish confirms that he’s not exactly a pure-bred Mancunian. In the States, the epitome of American art-punk was nervy, bug-eyed and above all Scottish-born David Byrne. A little later came Steven Patrick Morrissey, who for all his subsequent dubious flirtations with wrapping himself in the Union Jack was every bit as English in the fount of his wordsmithery as his idol, Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde – i.e. not very at all. Plus, of course, the Postcard Records stable – “the sound of young Scotland”, with the teenaged Edwyn Collins of Orange Juice to the fore. And there was also This “Blue Piano” from Montréal, Québec, led by Northern Irish émigré Steve Lamont.

And that’s the Greil Marcus bit over; the rest of this essay is pure matey gush.

In my early teens, at school in Belfast in the 1970s, Steve Lamont was my David Watts: “He is the head boy of the school/He is the captain of the team...” (oop, there goes Ray Davies again), except for the gay subtext. Steve had brains aplenty, athleticism in no small measure and a natural gift for friendship that meant his other talents never rendered him an outsider. And then, just as I’d begun to turn him away from heavy metal towards punk and its offshoots, he and his family buggered off across the Atlantic – or, in his words, “then I moved to Canada and became a dork.” Which latter point, naturally, drew us even closer together, save for the little matter of an ocean.

We kept corresponding, and met up again on his periodic trips back to the Auld Sod. We also each started making music of our own. But where I fumbled around with Ulsterpunk and then with early bleep-squark electronica, Steve actually took the effort to learn to play. While I more or less gave up on gigging and covered up my twelve-left-thumbs approach by making multi-track recordings on a twin-deck cassette machine in my bedroom (foisting the results on friends under the label of Cemental Health Records), Steve learned all those awkward chord shapes, formed a band called Exhibit A and put himself in front of audiences. My home-grown self-pity followed music journalist Andy Gill’s dictum that “most great rock’n’roll is just spotty adolescents whining on about not getting any” (except for the bit about great... or, for that matter, rock’n’roll), whereas Steve was already beginning to rip the piss out of the culture that he was still half-in, singing the self-mocking refrain, “I love my bedroom”.

A brief cover-versions collaboration on his 1982 visit to the homeland confirmed the way things were going: I opted for Talking Heads and Teardrop Explodes numbers and plonked away on bass, while Steve turned me on to Orange Juice and jangled and soared like a fledgling indie-pop angel.

By the following summer, when I made the trip to Canada, Exhibit A had undergone line-up changes and become This Blue Piano and then This “Blue Piano” (in deference to the typography in the source for the name, the opening stage direction of A Streetcar Named Desire), and had gelled into a classic indie power-plus-subtlety trio. On bass, Ken “Comrade” Ashdown nipped up and down the frets like a young gazelle. A gazelle with opposable thumbs, obviously. Ken had a wonderful brash charm: when we met, his first question to me was, “So, what’s your favourite vice?” (Utterly wrong-footed, I eventually stammered, “Uh... language, I guess.” Oddly, the obvious candidate – masturbation – never occurred to me, but I think my answer marked me out as a prime wanker anyway.) Likewise drummer Colin “Otis” Cahill: physically a great bear of a guy, temperamentally he was pure Tigger. TBP’s first official release, the cassette album Dick And Jane Eat God on their own Waste Island label, was recorded in Colin’s basement, but the inlay card refers to it as “Duffy’s Tavern/Radio Free Botswana”, after Otis’s habit of jocularly answering phone calls with one or the other.

Recorded on a four-track cassette PortaStudio, Dick And Jane is frankly sickening in its accomplishment. From the boppy opener I Before E (“about a girl whose name was spelt this way” –Steve) through to the semi-audible gasp of exultation that ends the simultaneously despairing and yearning Summertime, it’s a gem of its kind. Sex, love, politics, loss and fun all in counterpoise: the agony and the ecstasy. (The cover image was Michelangelo’s Creation Of Adam.) With Steve not yet twenty years old, he and the band had all but written the Bible on being a smart, feeling late-teen. This album’s opener Red Capital Letters comes from those sessions; alas, the version of City Of Tears included here is a later re-recording, so I can’t say, “You hear those swarms of irritated hornets in minor thirds in a shoebox in the next room? That’s me on synth, that is.”

The biblical motif continued with the band’s first vinyl release in mid-1984, The John The Baptist E.P. (secret, fuck-off arrogant title: The Beatles Were John The Baptist.) I remember the rush of excitement when I went into the mail room of the college I was then attending and saw the 12”-square package. (Honestly, can a CD-sized parcel give the same rush? I mean, really?) Its re-recordings of a couple of Dick And Jane tracks, plus the new Euphoria and the sublime Ground’s Gone, were astounding. It had pride of place on my student shelves even though I didn’t have a record deck with me at college.

Although they only ever released one further track officially – the version included here of Where Am I To Go? on a compilation album of Montréal bands – TBP’s craft went from strength to strength. The addition of Norman Mackay on keyboards and second guitar (the Garth Hudson of the band... well, not the Garth Hudson of The Band, obviously; Garth Hudson was the Garth Huds— shut up, Ian) bolstered their sound to a gorgeous lushness. Abortive negotiations with A&M Records yielded nothing but a platitude the band came to follow with a cheeky up-yours attitude: “Well, why don’t you write more songs with the title actually in the lyrics?” Five of the eleven tracks here come from a 1985 session that was so magnificent I couldn’t let them fester unheard, so Cemental Health Records (having previously also issued Dick And Jane in the U.K.) whacked out another TBP release. (There was also a posthumous collection, so that all these songs have already been released on CHealth, if not always in the same version; it was never a high-powered, operation, though, so if you’re looking for royalties, lads, they were the last round of drinks I bought you.)

Steve could (literally) summarise Proust and not be abstruse about it; first and foremost, it was rock music. He could turn out a tribute-to-the-band number that punned on the Russian for “blue piano”, likewise. When I wrote a Puritanical moral-high-ground song half-directed at him, I ripped off mid-period New Order and turned it into a throbby-bass dirge; his reply song knocked mine into the long grass by taking its chorus chords from Scott Walker’s The Girls From The Streets, and doing it full, glorious justice.

These were premier-league smarts, and I guess put TBP in towards the start of what in North America is now called, sometimes too glibly and disparagingly, “college rock”. But these guys were always buoyed up by a sense of levity, a sense that they had somewhere to go, a sense... I know it’s callow and adolescent, but what the hell, it’s time to dust the word off again: a sense of passion. And of course, Then I Saw You is just the finest three-minute pure pop single never to have been released, complete with its too-obvious-to-resist “na-na-na” harmonies and its P. Henry twist (one better than an O. Henry twist). To paraphrase fellow Montréaler Leonard Cohen, This “Blue Piano” took the business of songs and their subject matter both seriously and joyously at once.

Steve was the dominant songwriter, but Ken and Norman’s brace of tracks here stand up with the best of them: Falling Down Again can still bring a tear to my eye, and Serendip send me whirling in delight... which, with this middle-aged spread, is no mean feat, let me tell you.

Sadly, the breakthrough never came, and in 1986 they knocked it on the head. The quartet dispersed across the vastness of Canada, making periodic reunions for their own and close friends’ weddings. I count one such appearance (with the band augmented by sometime manager Lilly Buchwitz on backing vocals) among the finest live gigs I’ve ever seen; the sheer joy of hearing these songs performed to an audience, still as fresh and exuberant as they had been a decade earlier, was something to cherish. And I do; even after the passage of time has taken its toll on the regularity of our contact with one another, the love and wonder still shine through here. I know that other associates of the band, such as “fifth Piano” and spiritual advisor Ed “Finn” O’Connor have far more of a claim to involvement, but all the first-person faff in these notes is because I’m just so damn happy and proud to have been even on the periphery.

And now, twenty years after Dick And Jane Eat God, comes this first CD retrospective... which takes its title from a number not included on the album; up yours one more time, Mr A&M. Komrad has digitally cleaned up and tweaked the four-track demos and the sometimes stretched master tapes so that the songs glisten in all their ’80s chorus-guitar brightness. And I have the honour of being the evangelist, the heartfelt joy (that word again) of testifying to what you missed; but fuck it, you can hear that for yourself. Steve Lamont was one of the finest and most inspiring friends a young man could hope for, and This “Blue Piano” were and are a perfect soundtrack for a heart that never grows old, because nobody’s heart ever does. Thanks, Steve; thanks, guys. From the heart of me.

Ian Shuttleworth

London, England

May 2003

Le Spectrum, Montreal (special guests of Everything But the Girl)

about the author

Ian Shuttleworth writes for the London Financial Times as theatre, comedy and sometime live music critic, a post he has held since 1994, and is (joint) senior theatre critic 2007—. He is also Editor/publisher of Theatre Record magazine (since 2004) and has contributed to The Sunday Times, the Guardian, London Evening Standard, the Observer, the Independent, Daily Mail, Sun, Scotsman, The Stage and Private Eye, among other publications.

Mr. Shuttleworth's books include Ken & Em (an unauthorised Branagh/Thompson biography released in 1994) and was a major contributor to Reading The Vampire Slayer: An Unofficial Critical Companion To Buffy & Angel, the 2001 surprise best-seller (revised and updated second edn. 2004).

.